Few months back, I was sick and tired of writing work-related code, so I decided to start a side project just to revive the fun of programming in me. I had a bunch of ideas floating around in my head, but I eventually settled on creating my own tiling window manager from scratch because it was both practical and challenging. At work, I’d been diving into various spatial data structures, and one in particular caught my eye - the binary space partitioning tree (BSP-tree). I thought it would be perfect for a tiling window manager.

First things first, what is a tiling window manager?

Before I start talking about BSP-trees, what the heck is a tiling window manager? Fair question. Basically, it’s a type of window manager that organizes application windows in a non-overlapping manner. Unlike the usual window managers you see on OSx or Windows, where windows can stack on top of each other and overlap, tiling managers split your screen into tiles/sectons, each containing a window or a another split. As a user of a tiling window manager, you don’t have to think about where to place your windows, you just spawn a window, and bam! It’s automatically placed in the correct spot on your screen. If you’re using macOS or Windows, you’re most likely running a regular stacking window manager where windows can overlap each others.

These tiling managers are popular in the Linux world, but they’re not exclusive to it. I think there have been some attempts to bring DWM (a popular tiling manager) to Windows, but I can’t really vouch for how well it works. On Mac, there’s this tiling manager called Yabai that’s gained a lot of traction. It works as an extension to the built-in window manager, and from what I see online, it’s pretty solid.

Now, the basic idea behind tiling managers is simple, but actually implementing one can get a bit tricky. Some use linked lists to keep track of windows, while others use different types of trees. Personally, I think trees are a better fit for this kind of job. They’re naturally hierarchical, which matches up nicely with how windows are typically arranged on a screen.

The issue with linked-lists

Using a linked-list to manage windows has its drawbacks, even though it might seem easier to implement at first glance. The main issue is that linked lists are basically just a straight line of data (linear data structure). When we think about how windows are arranged on a screen, especially when they’re not overlapping, it’s clear that it’s not a simple line-up. Instead, they forms a more complex, multi-dimensional and hierarchical structure.

In fact, even with regular overlapping windows, you’ve got this whole complex spatial relationship going on. Some windows might be covering part of the screen, others might be hiding behind them, and some might be off in their own corner. This goes beyond simple linear ordering.

Because of this mismatch between the linear nature of linked lists and the multi-dimensional layout of windows, using them for window management means you end up having to do a ton of complicated math to figure out where everything should go. Every time you add a new window or close one, you need to recalculate all these rectangles to keep everything in place. You basically need to translate a one-dimensional data structure into a multi-dimensional screen layout, which is hard.

Trees actually handle it better!

Trees on the other hand are more intuitive in this context, they’re hierarchical by nature and can easily be used to emulate multi-dimensional screen layouts. The structure of a tree naturally maps to the way windows are typically arranged on a screen, you can use some nodes to represent different areas of the screen, and others to represent the actual windows. It’s a much more intuitive way to think about the layout, and it makes a lot of operations simpler to implement.

Binary space partitioning (BSP) tree

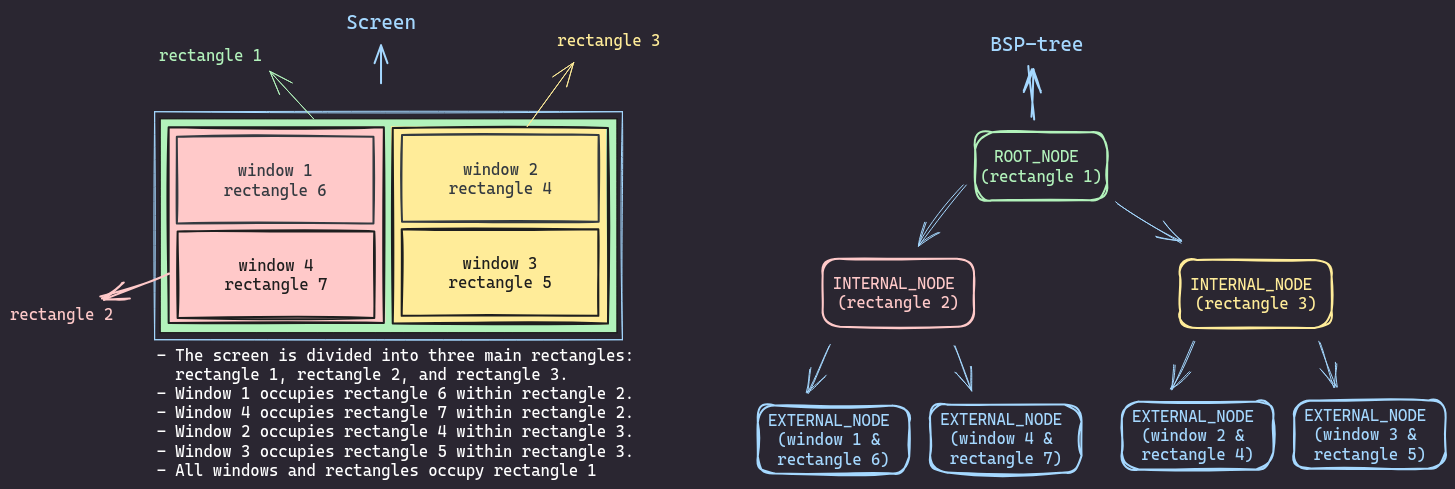

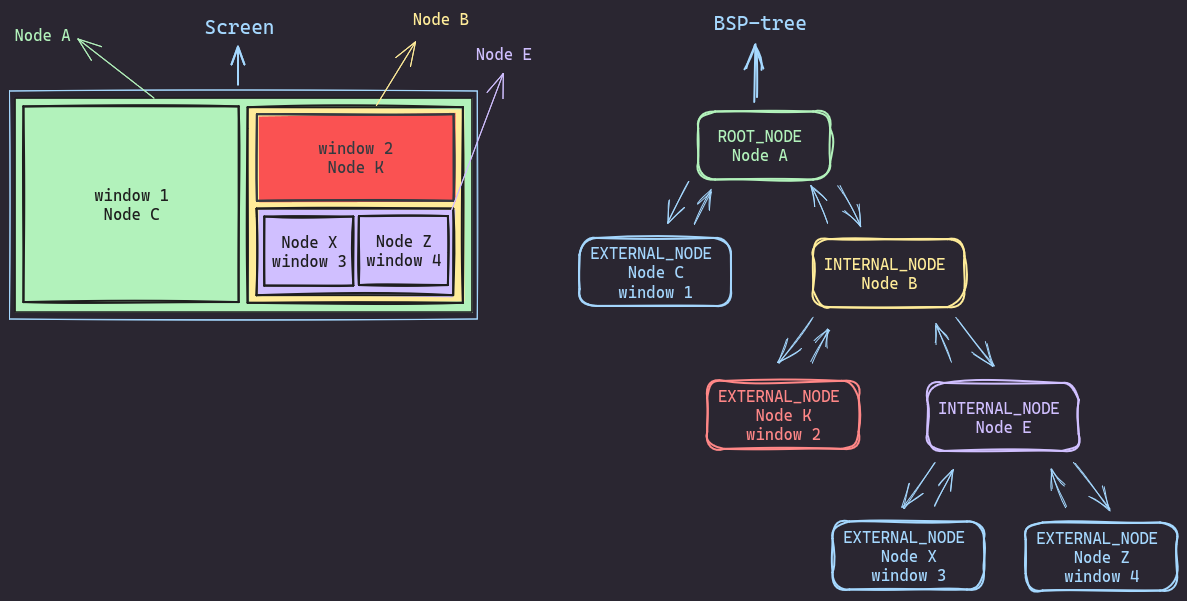

We’re talking about BSP-trees here. It’s a fancy name, but the concept is pretty straightforward. Imagine starting with your entire computer screen and drawing a vertical line to divide it in half. Then, you take each of those halves and split it again horizontally or vertically, keep doing this over and over, and you’ve got yourself a BSP tree. In this tree, the whole space (like your full screen) is the root, each split creates two new branches, and the smallest divisions become the leaves of the tree.

Now, in any tree structure, we have three types of nodes:

- The root - it’s the boss, sitting at the top.

- Internal nodes - they’ve got kids (other nodes) under them.

- External nodes (or leaves) - they don’t have any nodes under them.

In a BSP-tree, the internal nodes represent different sections of the screen, while the leaves represent actual application windows.

When I was building my own tiling window manager, I looked at a bunch of different ways people had implemented BSP trees. Most of the implementations I came across kept things pretty simple, they didn’t bother including a parent node in each node of the tree. Instead, the typical structure was something like this: each node would just keep track of its two children along with other implementation-specific data.

This approach was really common. I kept seeing it over and over in different implementations. They’d have the two child nodes and maybe some other stuff, but no direct link back to the parent.

So, a node in a BSP tree can be defined in two ways:

- Without a parent pointer:

typedef struct node_t node_t;

struct node_t {

node_t *first_child;

node_t *second_child;

client_t *client; // window

node_type_t node_type;

rectangle_t rectangle;

rectangle_t parent_rectangle;

...

};

- With a parent pointer:

typedef struct node_t node_t;

struct node_t {

node_t *parent;

node_t *first_child;

node_t *second_child;

client_t *client; // window

node_type_t node_type;

rectangle_t rectangle;

...

};

The approach without a parent pointer is simpler and uses less memory. But it has some drawbacks. When you’re adding new nodes or doing other operations like resizing or splitting, you need to explicitly pass along the parent’s rectangle info (this isn’t a real problem but I am lazy I guess). And when you want to check if a sibling is external or internal, well good luck with that, you end up writing a bunch of code just to access the sibling. Plus, if you ever need to move up the tree, you might need to get creative or use some extra data structures or complicated algorithms that I can’t come up with.

On the other hand, including a parent pointer uses a tiny bit more memory, but it makes life so much easier in other ways. Need to move up the tree? No problem. Checking siblings? Piece of cake. The only real downside is that you’ve got to be extra careful when you’re deleting nodes so that you don’t leave dangling pointers behind.

In my implementation, I chose to include the parent pointer. Yeah, it uses slightly more memory, but the ease of use and simpler coding made it totally worth it (again, im lazy).

Using a BSP-tree to manage windows

When it comes to actually managing windows with a BSP-tree, there’s a lot to consider. I’ll walk you through how I handle inserting and deleting windows in my implementation. Keep in mind, this might not be the most optimal approach for every situation, but it worked well for what I needed and I don’t care.

Insertion in a BSP-tree

To understand the insertion process in a BSP-tree, let’s start by defining the rules for the tree:

- The tree is a partition of a monitor’s rectangle into smaller rectangular regions.

- Each leaf node holds exactly one window.

- Each node in a bsp-tree either has ZERO or TWO children.

- Each internal node is responsible for splitting a rectangle in half.

Window Split logic

Now, here’s the logic for doing all the partitioning:

Let’s say you have a node (we’ll call it Node X) that’s currently holding a window. Then you decide to open a new window (let’s call this one Node B). What happens is simple. Node X goes from being a simple leaf to becoming a parent (from external to internal) and the window it was holding gets moved into a new child node (Node A), and your new window becomes its other child (Node B).

Node X’s rectangle then gets split in half to make room for both of these new nodes. When we split Node X’s rectangle, we look at its dimensions to decide whether to cut it horizontally or vertically, If it’s taller than it is wide, we’ll cut horizontally, otherwise we’ll cut vertically. This split ends up creating two new rectangles for Node A and Node B, and both of these new rectangles fit entirely within Node X’s original space.

As you can tell, rectagnles can contain other rectangles or be contained wihin other rectangles.

Let’s look at some code for inserting and splitting:

void

split_node(node_t *n)

{

// vertical split (side by side)

if (n->rectangle.width >= n->rectangle.height) {

// set up the first child (left side)

n->first_child->rectangle.x = n->rectangle.x;

n->first_child->rectangle.y = n->rectangle.y;

n->first_child->rectangle.width = n->rectangle.width / 2;

n->first_child->rectangle.height = n->rectangle.height;

// set up the second child (right side)

n->second_child->rectangle.x = n->rectangle.x + n->first_child->rectangle.width;

n->second_child->rectangle.y = n->rectangle.y;

n->second_child->rectangle.width = n->rectangle.width - n->first_child->rectangle.width;

n->second_child->rectangle.height = n->rectangle.height;

} else { // horizontal split (top and bottom)

// set up the first child (top)

n->first_child->rectangle.x = n->rectangle.x;

n->first_child->rectangle.y = n->rectangle.y;

n->first_child->rectangle.width = n->rectangle.width;

n->first_child->rectangle.height = n->rectangle.height / 2;

// set up the second child (bottom)

n->second_child->rectangle.x = n->rectangle.x;

n->second_child->rectangle.y = n->rectangle.y + n->first_child->rectangle.height;

n->second_child->rectangle.width = n->rectangle.width;

n->second_child->rectangle.height = n->rectangle.height - n->first_child->rectangle.height;

}

}

void

insert_node(node_t *existing_node, node_t *new_node)

{

if (existing_node == NULL || existing_node->client == NULL || new_node == NULL) {

_LOG_(ERROR, "Invalid node or client");

return;

}

assert(existing_node->node_type = EXTERNAL_NODE);

// set existing_node type to INTERNAL_NODE

if (!IS_ROOT(existing_node)) {

existing_node->node_type = INTERNAL_NODE;

}

// move existing_node client data to the first child

existing_node->first_child = create_node(existing_node->client);

if (existing_node->first_child == NULL) {

return;

}

existing_node->first_child->parent = existing_node;

existing_node->first_child->node_type = EXTERNAL_NODE;

existing_node->client = NULL;

// assign the new node as the second child

existing_node->second_child = new_node;

existing_node->second_child->parent = existing_node;

existing_node->second_child->node_type = EXTERNAL_NODE;

// split

split_node(existing_node);

}

I know code can be a bit overwhelming sometimes, so let’s walk through this BSP-tree concept with some visuals. It’ll make things much clearer.

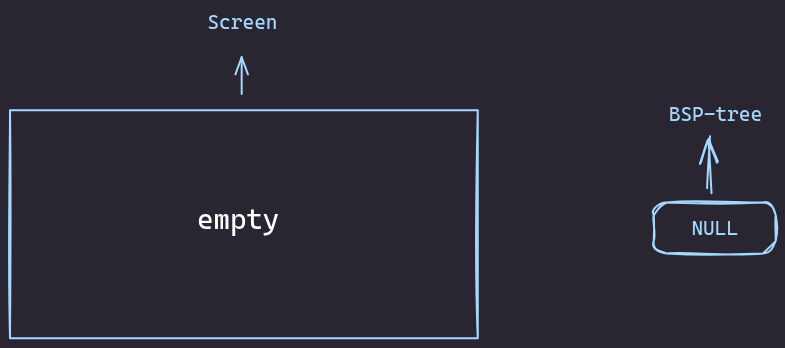

You’re starting with a completely empty screen. In BSP-tree terms, this is super simple - it’s just a single node marked as NULL and It would exactly look like this:

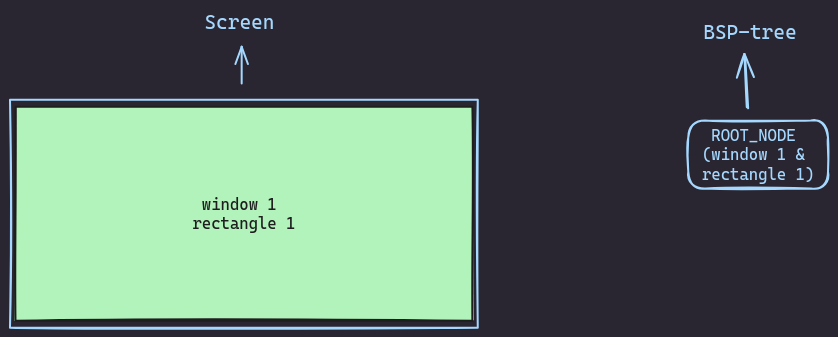

Adding the First Window

Now, let’s say you open your first window. Boom! It takes over the entire screen.

In our BSP tree, this becomes the root node. It’s got all the info about the window and covers the whole screen.

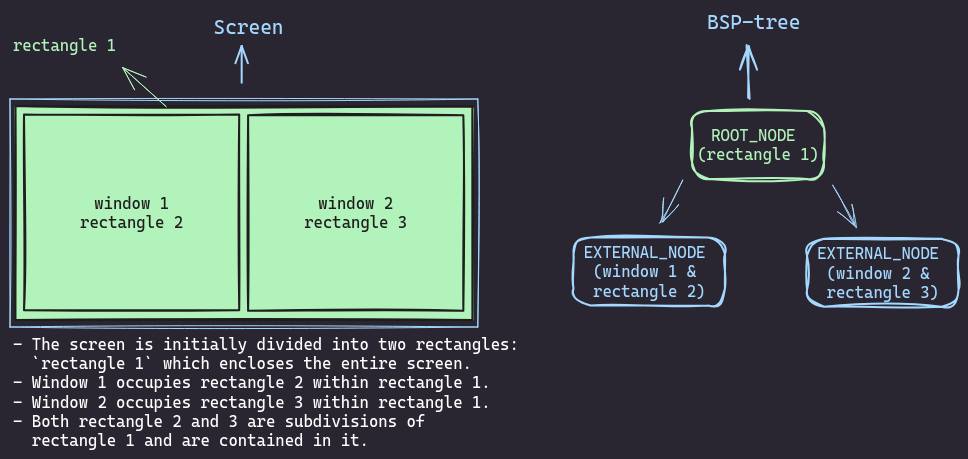

Adding the Second Window

Things get more interesting when you open a second window. The BSP tree gets clever here. It splits the screen in two, creating two child nodes under the root. Your first window slides into one of these nodes, and the new window goes into the other.

The root node is now overseeing both children but not directly containing a window itself.

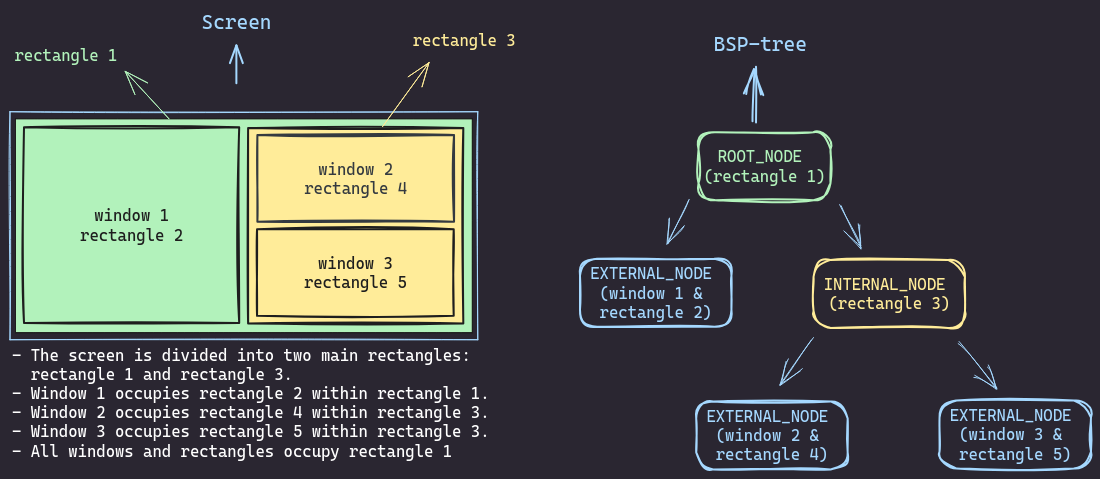

Adding the Third Window

Adding a third window gets even more interesting.

We pick one of the existing nodes (in this case, the right one) and splits it again. Now we’ve got three leaf nodes, each with a window, and a couple of internal nodes keeping things organized.

Adding the Fourth Window

By the time you get to four windows, you can really appreciate the system. The tree splits another leaf node, and now you’ve got this neat structure with four windows, each in its own leaf node, and a few internal nodes managing the layout.

Every time the tree splits, it’s making a decision to divide the screen either horizontally or vertically. No matter how many windows you open, the tree can always find a way to divide up the screen. And when you want to close a window or resize things? You just need to reuse the parent’s rectangle of your targeted node.

Deletion in a BSP-tree.

When deleting a node from the tree, we encounter two main scenarios:

- The targeted node has an external sibling.

- The targeted node doesn’t have a grandparent.

- The targeted node has a grandparent (its parent is the root of the tree).

- The targeted node has an internal sibling.

- The targeted node doesn’t have a grandparent.

- The targeted node has a grandparent (its parent is the root of the tree).

Let’s look at how these scenarios can be handled:

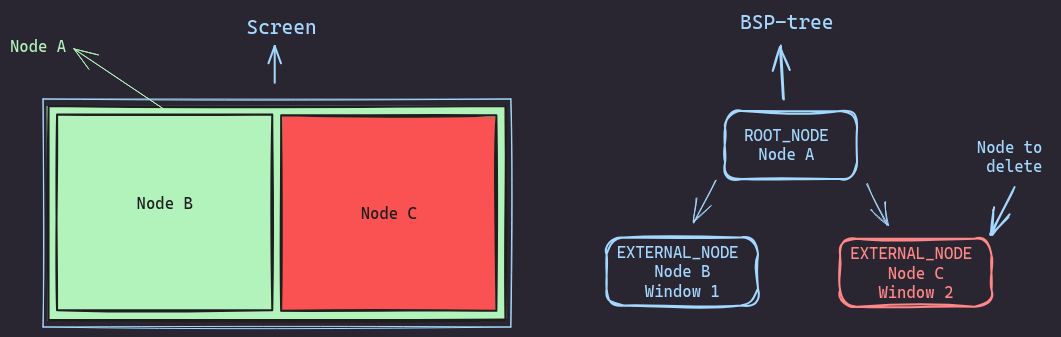

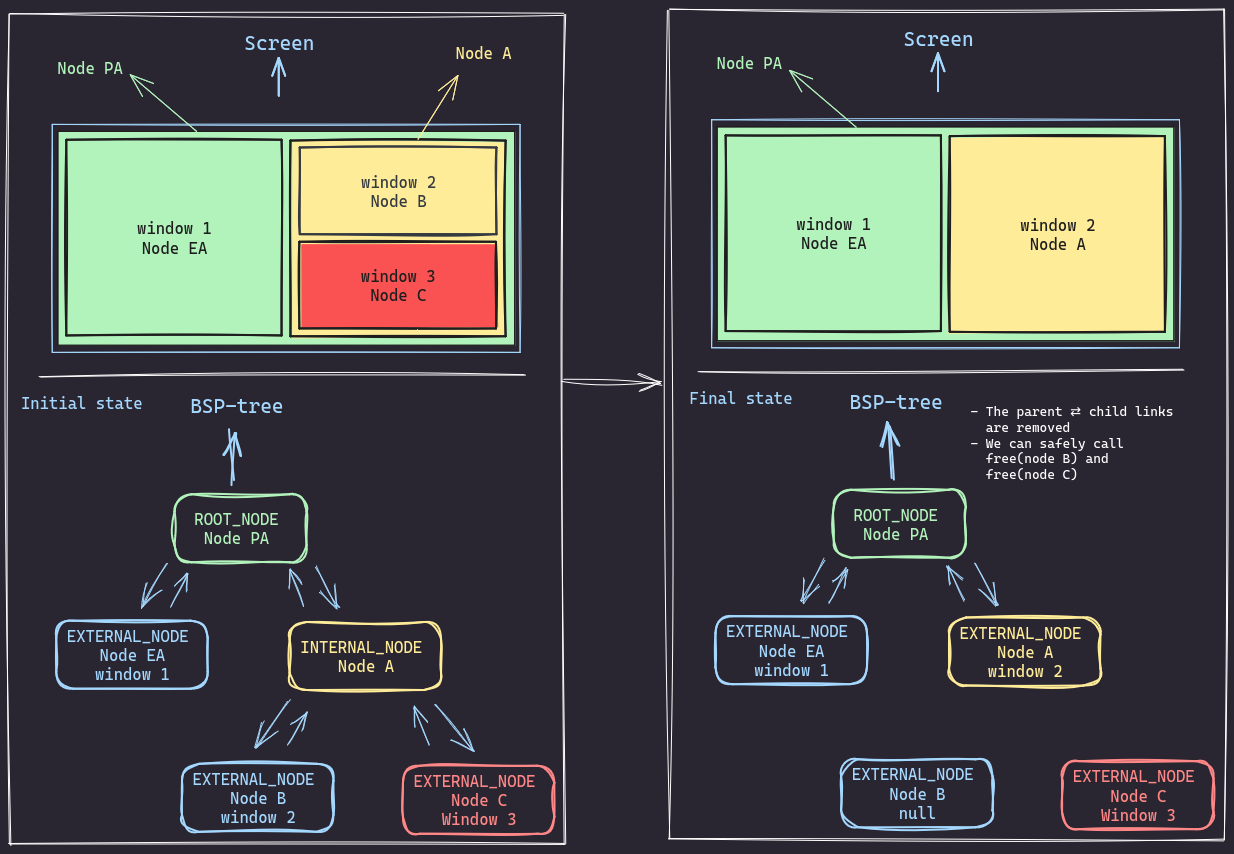

Case 1: External Sibling

External Sibling with No Grandparent

Let’s consider the following scenario. We have Node C, and it’s got an external sibling and no grandparent! How can we remove it from the tree?

- We want to delete

Node Cfrom the tree - First, we need to remove the

parent-childlinks betweennode Aandnode C.- We basically need to set child->parent to NULL and parent->child to NULL as well.

- Now we have the links removed, we move the window from

node Btonode A,node Bbecomes empty. - Now that

node Bis practically empty, we can remove the parent-child links betweennode Aandnode B. - Both

node Bandnode Cwill be unlinked from their parentnode A. - We can safely free

node Bandnode Cand resize the tree if we need to.

The difference between the initial and final state is as follows:

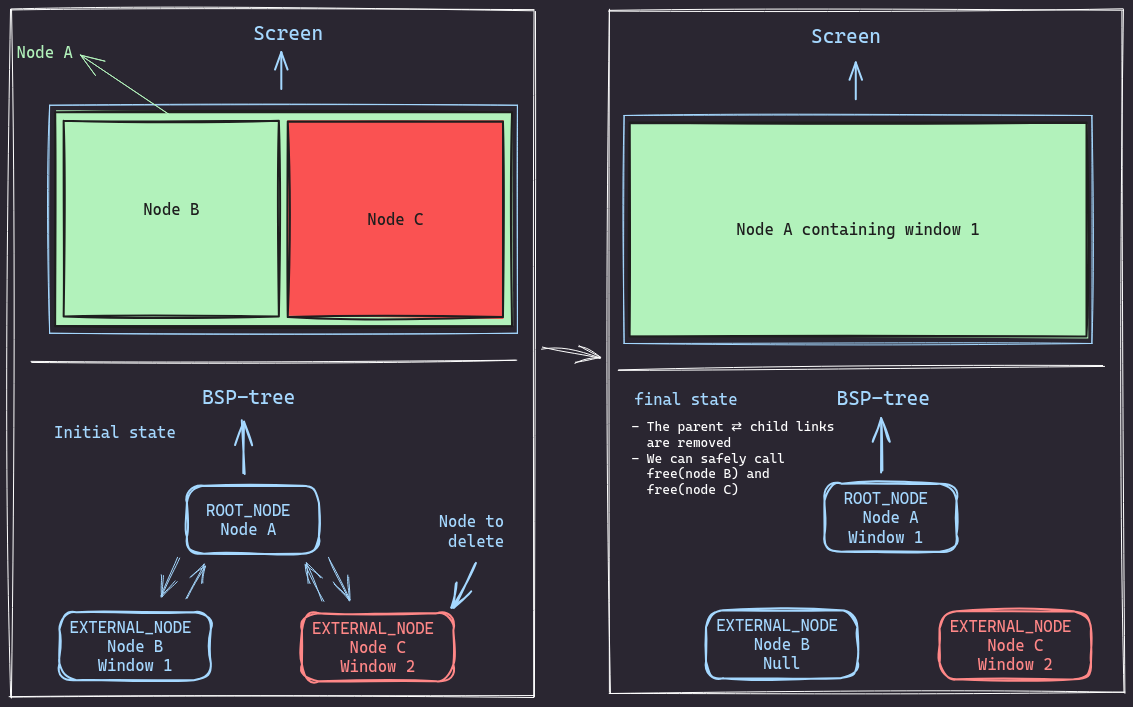

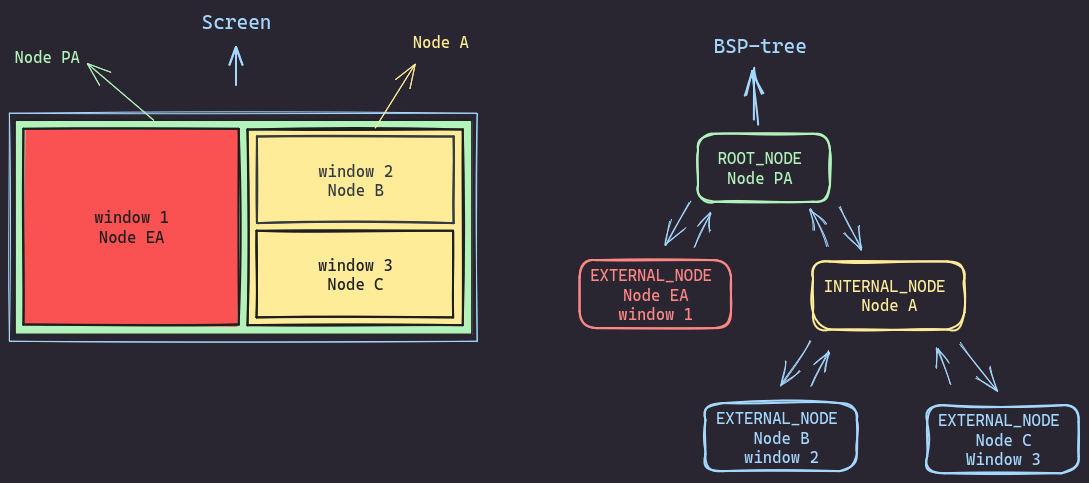

External Sibling with Grandparent

Let’s consider another scenario. We have Node C, and it’s got an external sibling and a grandparent! How can we remove it from the tree?

- We want to delete

Node Cfrom the tree - First,

node Ais internal, it represents a rectangle in the screen we aim to make it external by deleting its children and inserting a window in it - We start by removing the parent-child links between

Node A⇄Node CandNode A⇄Node B.- We basically need to set child->parent to NULL and parent->child to NULL as well.

- Now we have the links removed, we move window 2 from

node Btonode A,node Bbecomes empty. - Both

node Bandnode Cwill be unlinked from their parentnode A. - We can safely free

node Bandnode Cand do resizing if needed. - Finally we change

node Atype fromINTERNAL_NODEtoEXTERNAL_NODE

The difference between the initial and final state is as follows:

The code for both scenarios will pretty much look like this:

if (is_sibling_external(node)) {

node_t *e = get_external_sibling(node);

if (e == NULL) {

return;

}

// if I has no parent

if (IS_ROOT(node->parent)) {

node->parent->client = e->client;

node->parent->first_child = NULL;

node->parent->second_child = NULL;

} else {

// if I has a prent

node_t *g = node->parent->parent;

if (g->first_child == node->parent) {

g->first_child->node_type = EXTERNAL_NODE;

g->first_child->client = e->client;

g->first_child->first_child = NULL;

g->first_child->second_child = NULL;

} else {

g->second_child->node_type = EXTERNAL_NODE;

g->second_child->client = e->client;

g->second_child->first_child = NULL;

g->second_child->second_child = NULL;

}

}

e->parent = NULL;

free(e);

e = NULL;

node->parent = NULL;

free(node);

node = NULL;

}

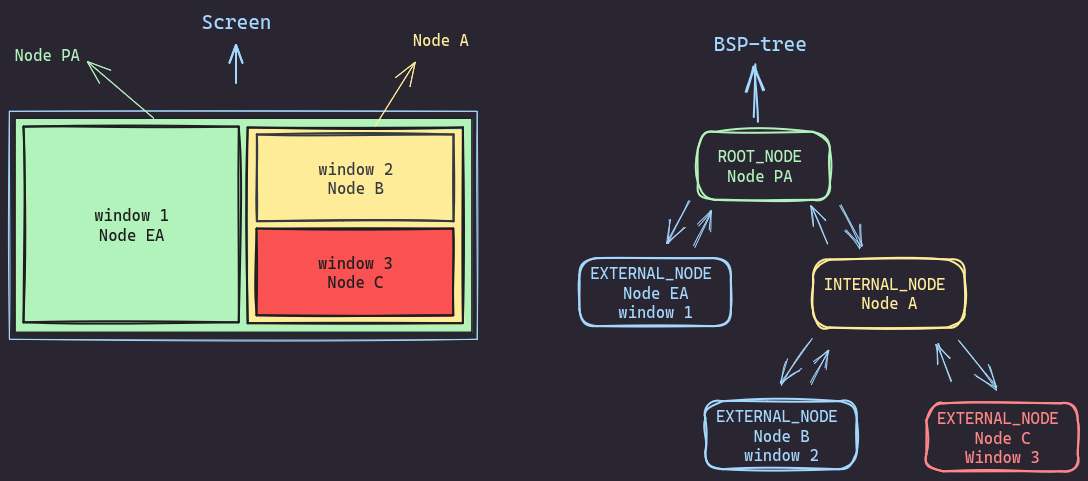

Case 2: Internal sibling

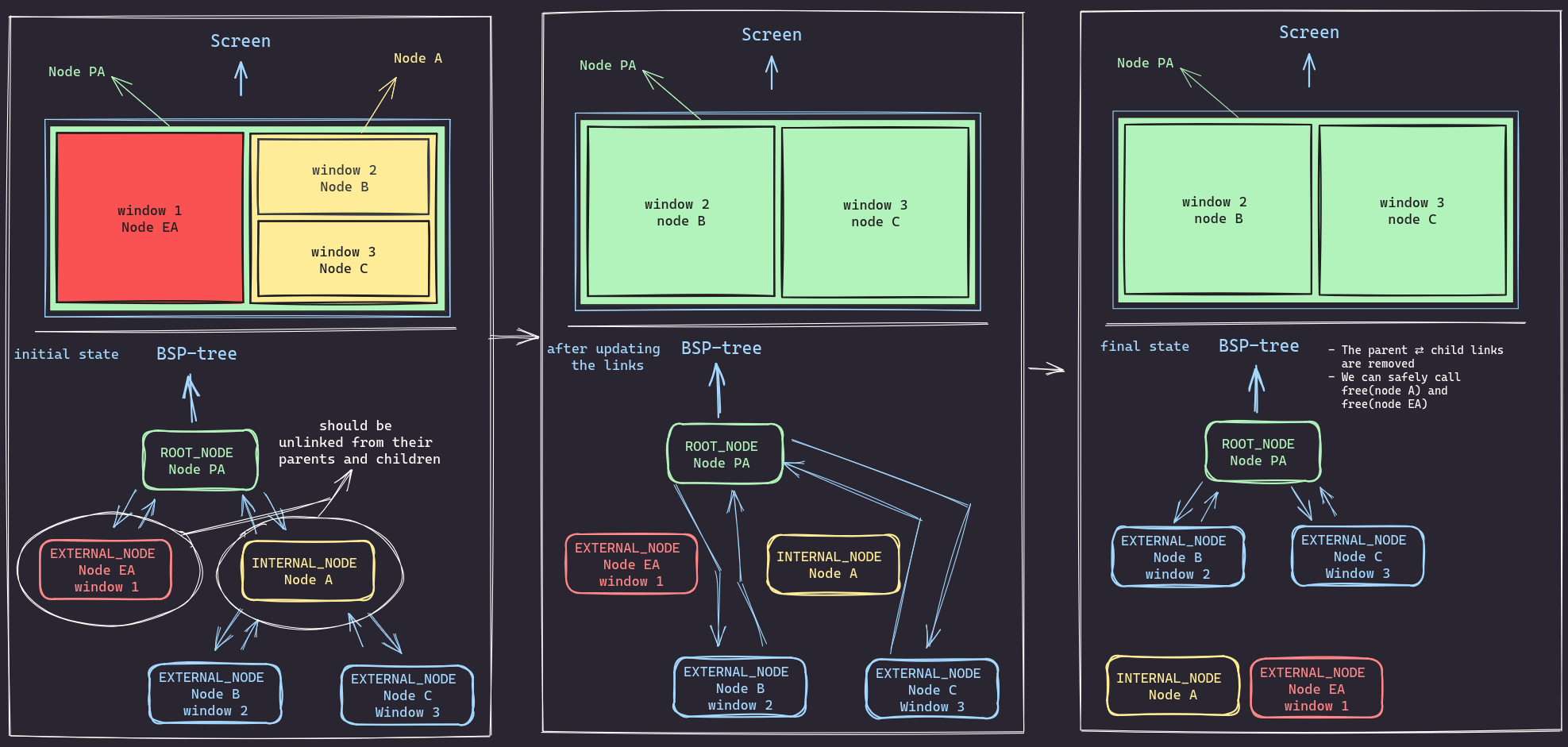

Internal sibling with no grandparent

Now if the targeted node has a an internal sibling, then a little extra work is required

Lets consider the following scenario, we want to delete Node EA (window 1) from the tree. but its siblingNode Ais an internal node with children (Node B and Node C).

How can we delete it?

- We want to delete

Node EA (window 1)from the tree. However, its siblingNode Ais an internal node with children(Node B and Node C). - The goal is to restructure the tree so that

Node B (window 2)andNode C (window 3)become direct children ofNode PA, and then removeNode EAandNode Aentirely. - First,

Node Ais an internal node representing a rectangle in the screen. To deleteNode A, we need to first unlink it from its children. - We start by removing the parent⇄child links

between (

node A⇄node Candnode A⇄node B).- We basically need to set child->parent to NULL and parent->child to NULL as well.

- Then we remove the parent⇄child links between (node PA ⇄ node EA and node PA ⇄

node A).- again we basically need to set child->parent to NULL and parent->child to NULL as well.

- Finally we link

Node CandNode BtoNode PA - After all that we free

Node AandNode EAand resize the tree

The difference between the initial and final state is as follows:

Or a shorter version:

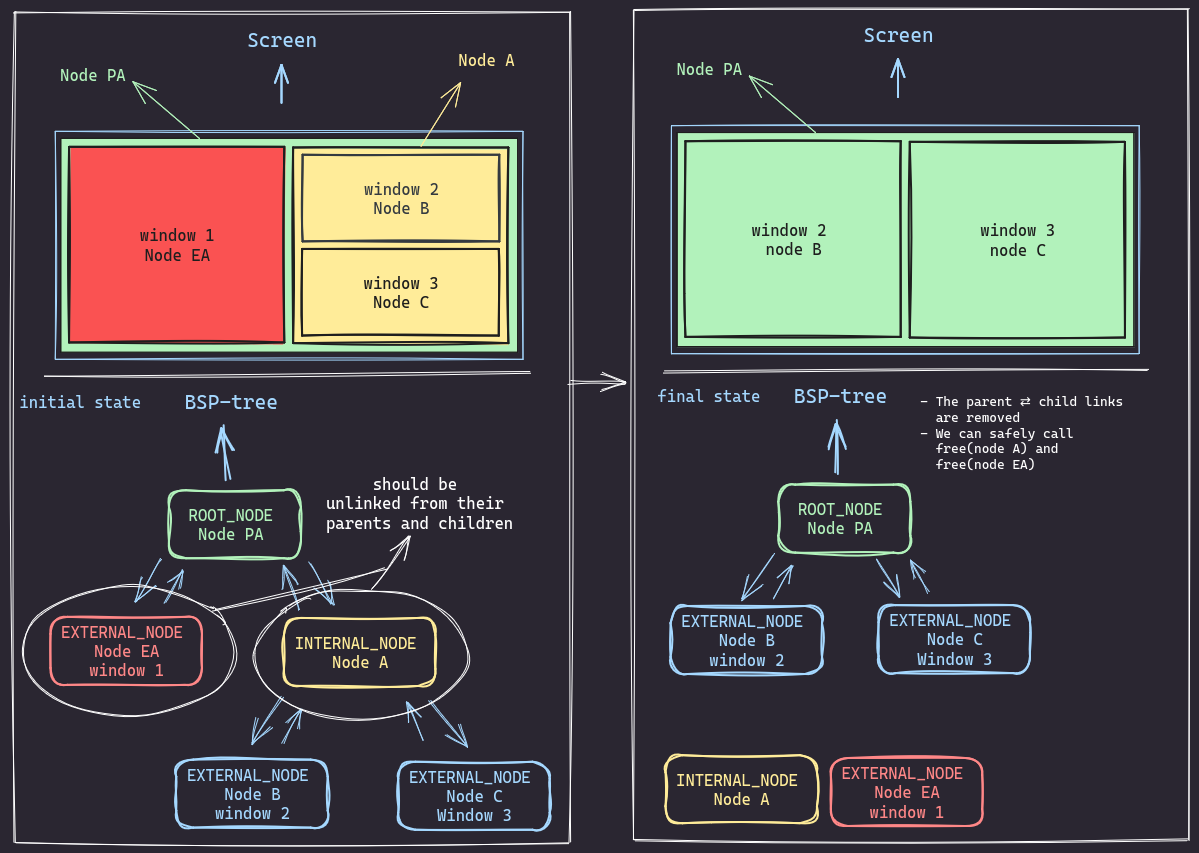

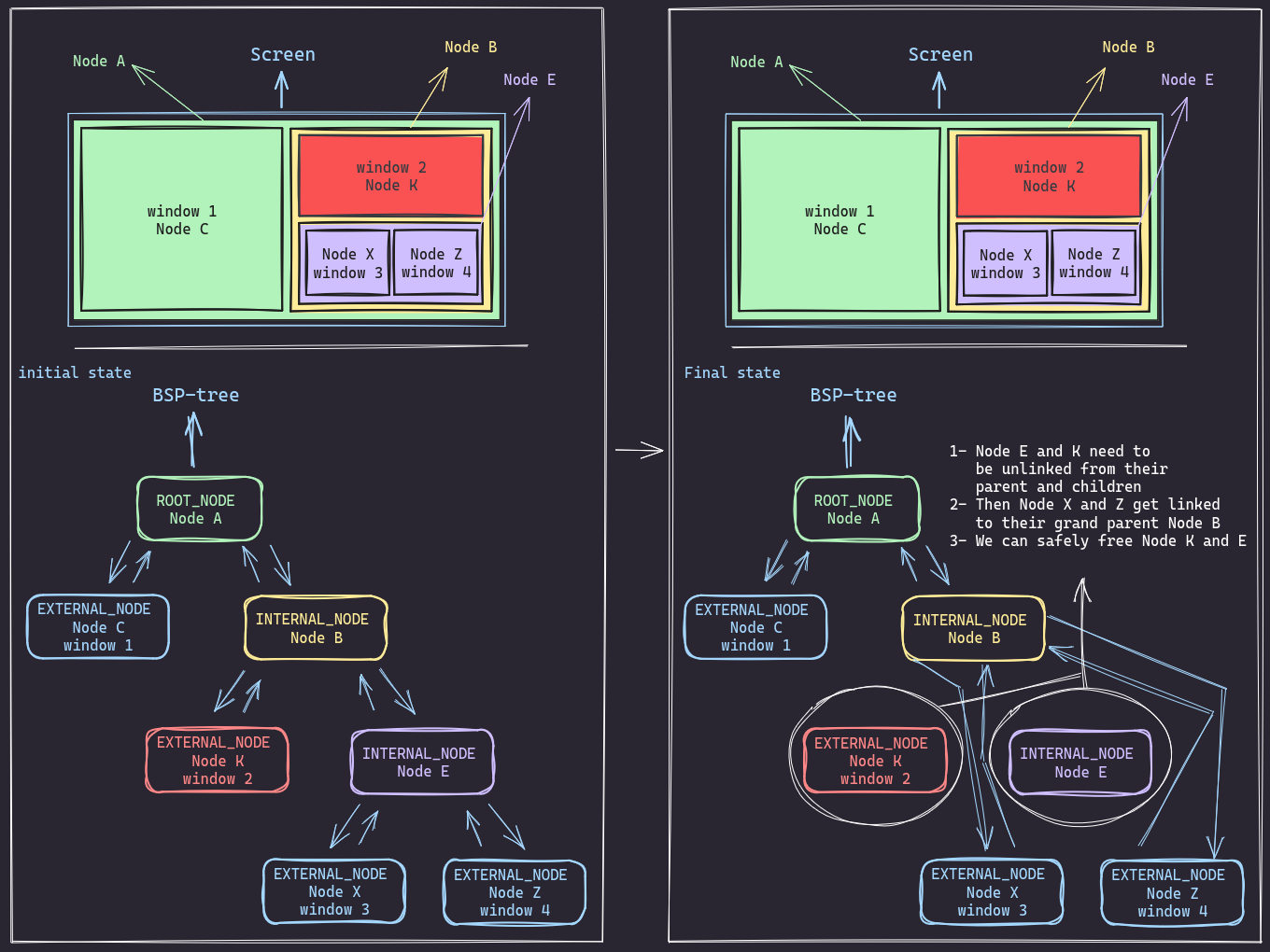

Internal sibling with grandparent

Now if the targeted node has a an internal sibling, and a grandparent then the logic will prety much be the same. We just need to find the psrent of the targeted node, get rid of the targeted node and its sibling then and link its children to the targeted node’s parent (to their grandparent).

Just like what the visual show, this is the initial state:

And this is how things look at the end:

The code for both scenarios will pretty much look like this:

if (is_sibling_internal(node)) {

node_t *n = NULL;

// if IN has no parent

if (IS_ROOT(node->parent)) {

n = get_internal_sibling(node);

if (n == NULL) {

_LOG_(ERROR, "internal node is null");

return;

}

if (d->tree == node->parent) {

d->tree->first_child = n->first_child;

n->first_child->parent = d->tree;

d->tree->second_child = n->second_child;

n->second_child->parent = d->tree;

} else {

d->tree->second_child = n->first_child;

n->first_child->parent = d->tree;

d->tree->first_child = n->second_child;

n->second_child->parent = d->tree;

}

} else {

// if IN has a parent

if (is_sibling_internal(node)) {

n = get_internal_sibling(node);

} else {

_LOG_(ERROR, "internal node is null");

return;

}

if (n == NULL)

return;

if (node->parent->first_child == node) {

node->parent->first_child = n->first_child;

n->first_child->parent = node->parent;

node->parent->second_child = n->second_child;

n->second_child->parent = node->parent;

} else {

node->parent->second_child = n->first_child;

n->first_child->parent = node->parent;

node->parent->first_child = n->second_child;

n->second_child->parent = node->parent;

}

}

n->parent = NULL;

n->first_child = NULL;

n->second_child = NULL;

node->parent = NULL;

free(n);

n = NULL;

free(node);

node = NULL;

}

Cool fact about the tree.

Hopefully, by now, you can see that continuously opening windows on one side of the screen won’t result in an extremely skewed tree forming a linked list. This is because BSP tree nodes can ONLY have two or zero children.

But, we can easily end up with an unbalanced tree, we need to write a balancing algorithm to fix it.

The end

So, there you have it. Using bsp-trees for managing windows in a tiling window manager isn’t just a fancy idea — it actually makes a lot of sense. I had so much fun Implementing this tree into my window manager, I learned a lot and banged my head against the wall more than a few times, but in the end, it was all worth it.